The topic of the ever-changing workplace is not exactly new. In fact, eight years ago, in an article for the Huffington Post titled “Work is a Verb,” I wrote: “Work is no longer just some place we go, but something we do and something we do in many different places that is hard to put a neat box around.” This transformation has long been under way, but the past two years have only accelerated the adoption of emerging ideas like hybrid work. So much so that many of our “best practices” in workplace design no longer apply.

Soon, “the hybrid workplace” won’t be a buzzy new phrase — it will just become “the workplace.” Work will continue to happen as a verb and not just a noun, but today we’ll be exploring the noun. How does the physical space where we gather to work and collaborate need to adjust and respond?

Soon, “the hybrid workplace” won’t be a buzzy new phrase — it will just become “the workplace.” Work will continue to happen as a verb and not just a noun, but today we’ll be exploring the noun. How does the physical space where we gather to work and collaborate need to adjust and respond?

We set out to answer this question as part of ThinkLab’s 10 bold predictions for 2022, based on our research of the design ecosystem. While we’ve talked plenty about strategies to create digital equity and policy changes to thrive in a hybrid work era, it’s time to examine the impact of hybrid on physical space.

Which brings us to Bold Prediction #3: Recent workplace policy and preference changes will trigger a hybrid butterfly effect of shifts.

According to a recent HBR article, more than 50 percent of companies “plan to pilot new workspaces” as they move to a hybrid model. This means a big opportunity for designers and architects — and the product manufacturers that serve them — to be on the forefront of a new era of experimentation and exploration and to define the next generation of best practices in workplace design.

Here are five questions that we think represent the biggest opportunities for exploration in workplace design:

- What is the right balance between collaboration and individual work?

- How might physical space layouts better foster trust and autonomy and create community?

- How might meeting space evolve?

- How might “measures of success” evolve to focus on effectiveness over efficiency?

- How might we design physical space to be flexible and evolve with us in an era of disruptions?

We recently sat down with Kate Lister, president of Global Workplace Analytics, who has spent the past 20 years exploring hybrid work, and Dagnall Folger, co-founder of A+I, a design agency focused not only on strategy, design, and architecture for space, but also the public space that links them. We’ll explore their perspectives and leave you with inspiration for challenging your teams to create the future of workplace design.

Finding the right balance between collaboration and individual work.

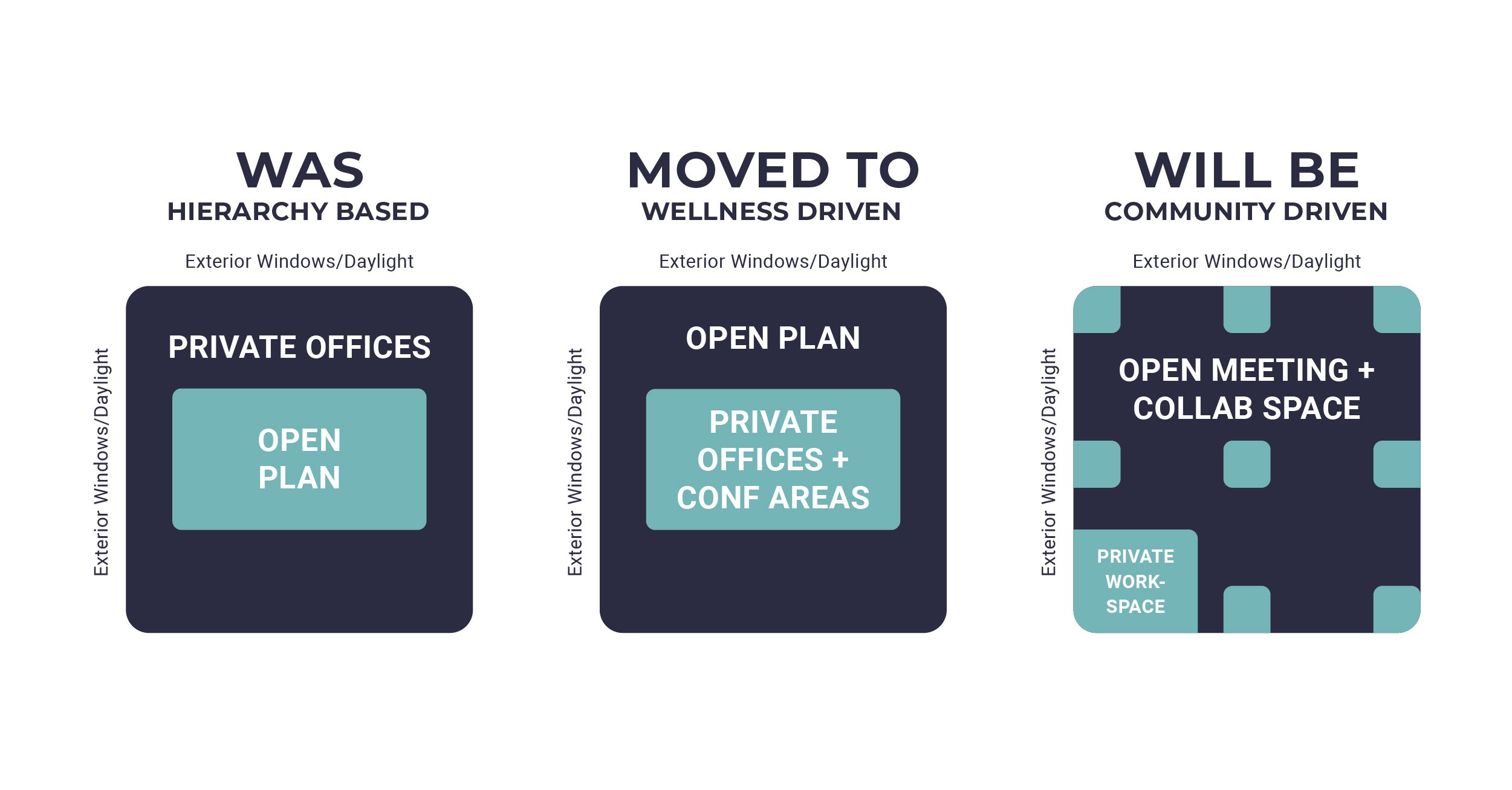

Folger shares: “We are in a profound moment in the transformation of work. For the last year and a half, we have seen all the leadership talking about policy change and aspirations for company futures. However, the real estate cycles are not at the same pace as policy change, so there is going to be a huge lag in the offices that people are coming back to. People are coming back and realizing that 70 percent of the real estate is [made up of] individual stations, and that doesn’t make sense.”

Kate Lister’s prediction: Coming out of the pandemic, 25 percent to 30 percent of the workforce will work remotely at least part of the week.

While many are discussing “the Great Resignation,” Lister urges us to think of it as “the Great Reevaluation.” Many people don’t want to give up the work-life balance and flexibility they have gained, both of which will contribute to future business success, as we consider upcoming space and policy changes.

Kate shares, “I don’t know if [this level of hybrid work would remain] if we weren’t in a talent crisis, but for now the employee is in the driver seat and they are wanting choice. Over the past two years, strong ties have gotten stronger, but weak ties have gotten weaker. We are missing community, and we don’t know how to effectively create that remotely. So, we still need physical space to connect.”

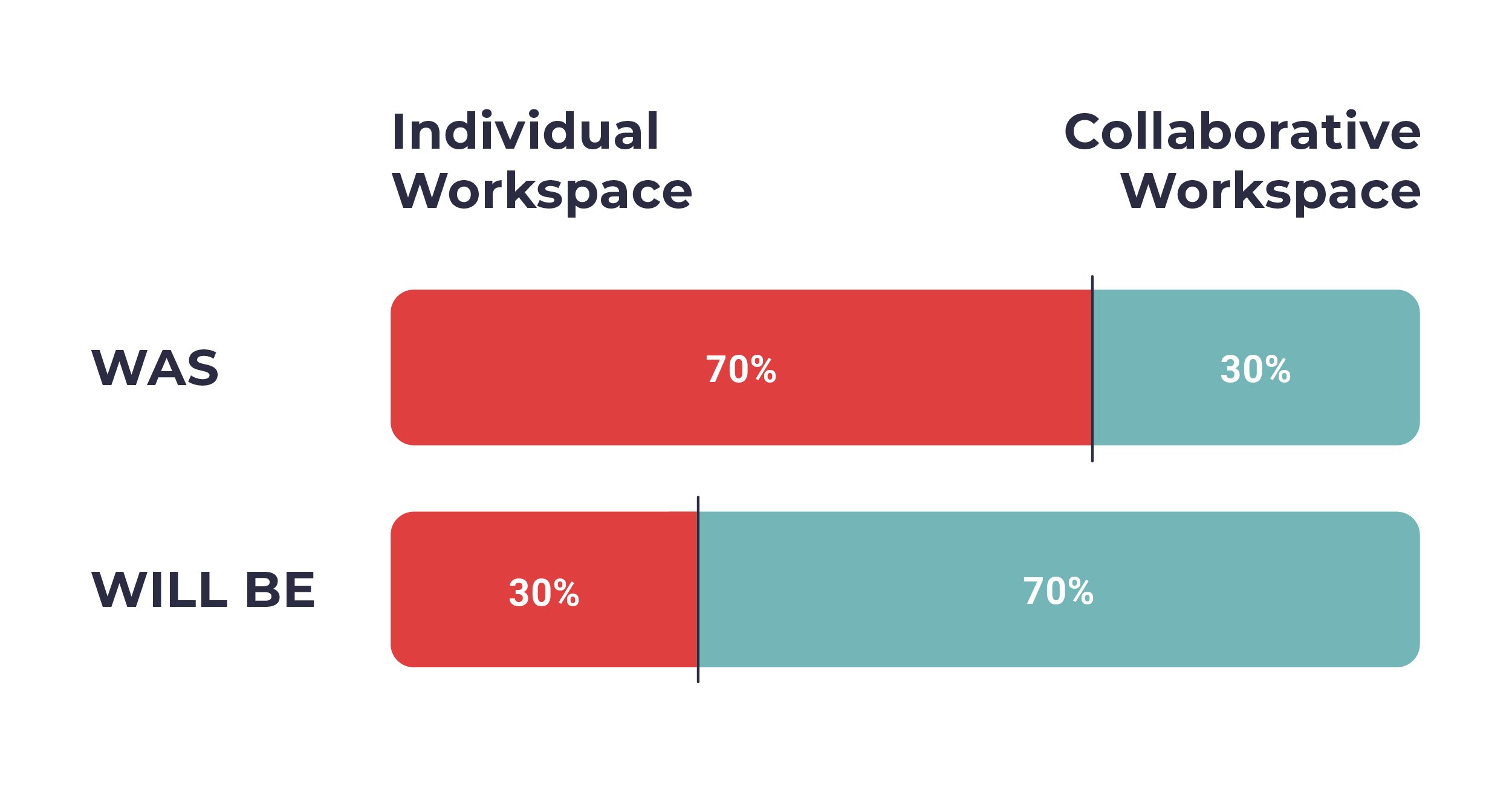

That balance may be different for each company, but our experts suggest that in these next few years, offices will favor collaborative space over heads-down space, moving from 70 percent individual work/30 percent collaborative to 30 percent individual work/70 percent collaborative.

Foster trust and autonomy and create community with physical space layouts.

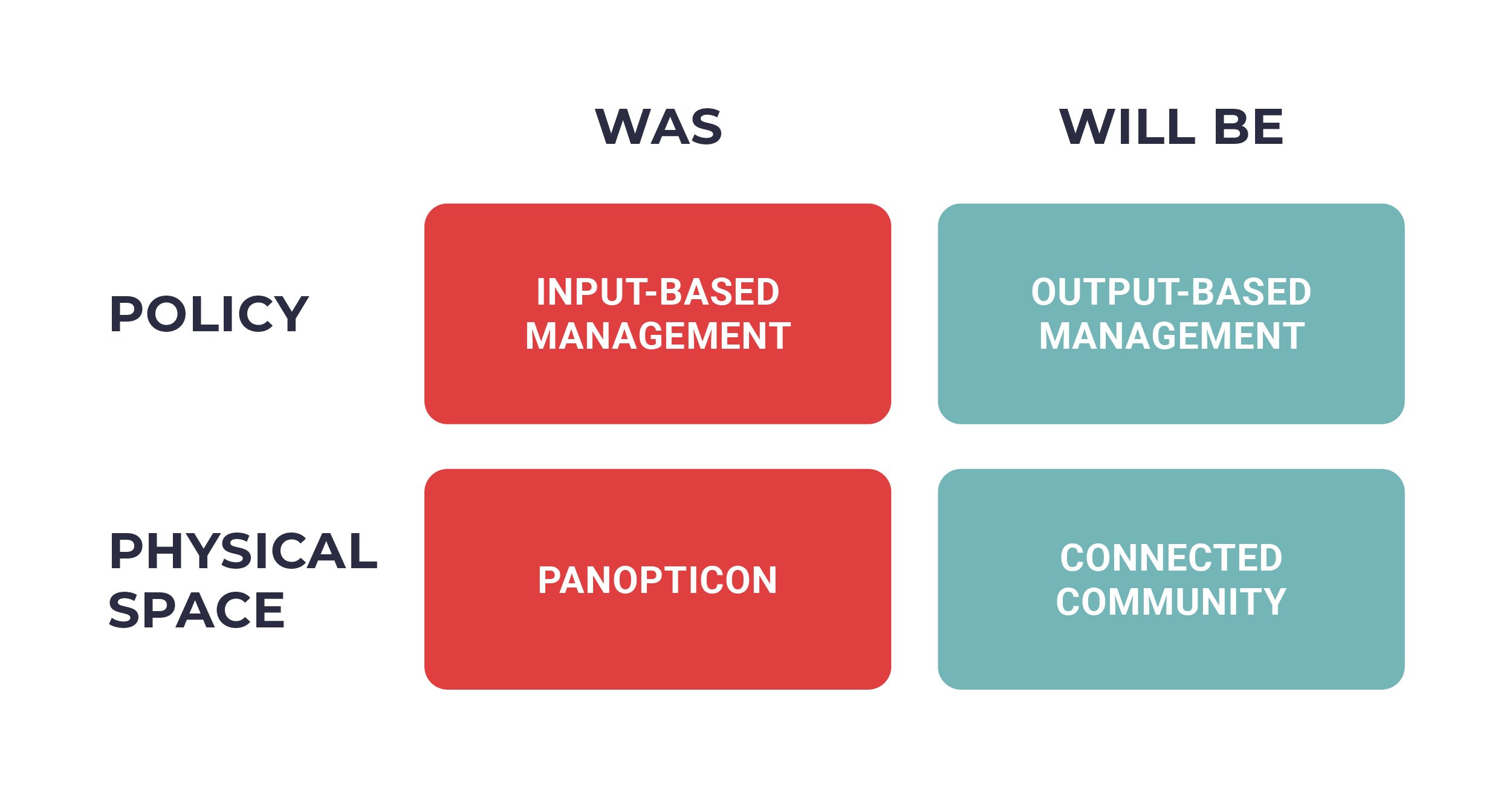

Folger urges us to explore not just evolution, but revolution: Instead of just trying to modify an existing model, we should be “building entirely new paradigms around communication and workflow, rather than a panopticon where there is no trust.”

Part of that means granting workers more autonomy. As Folger puts it, “Hybrid [work] has everything to do with trust — it’s a whole new path.”

A recent HBR podcast with Stanford professor Nicholas Bloom suggests managers evaluate their people in one of two ways:

- Input-based management: Manage by looking at what employees doing. Do they seem to be at their desk, working hard, furiously typing away, appearing to be productive?

- Output-based management: Manage based on the output employees produce. Do they hit their sales targets? Do they get their reports written? Do they produce new products on time?

Under a hybrid model, managers must rely on evaluating output when their employees are out of sight, which, as Lister points out, means people must perform: “Hybrid work doesn’t create problems; it gives them nowhere to hide. When you are based on output, you are either doing your job or you’re not.” Folger also adds that physical space needs to evolve in response to hybrid: “The office hasn’t changed in 100 years. The conference room, private offices, and open offices have all been the same vocabulary for 100 years. We are ready to break that open and create new ways of coming together.”

A recent HBR article suggests one key element will be remembering that collaboration requires individual work, too. Employees should be able to easily move between “we” and “me” time without trekking across campus or getting hung up on complicated technology. This is not the time to abandon workplaces. Quite the opposite: going to the office has never been just about work — it’s also about the connections, socialization, trust, and innovation that happens as you work. We need to develop spatial vocabulary that encourages even more of that.

We challenge that many offices are created for input-based management, but key to the success of our collective future will be redesigning the office “panopticon” away “management by eyeball.” We’ll need to grant the worker autonomy, with seamless transitions between home and the workplace; foster community in teams; and build trust with organizations in new ways.

Evolution of meeting spaces.

“A conference room is a broken model that enforces a power structure,” Folger contends. Amid the current integration of technology and physical space, with remote employees joining in-person meetings virtually, this imbalance is becoming more pronounced. Many have had the awkward experience of dialing into an in-person meeting as one of the only remote employees.

Common challenges to hybrid work meetings include:

- Trouble hearing

- Lack of visual cues about when to speak up

- The awkward realization that your face is on a jumbotron in the office (filters anyone?), while your coworkers’ full-body images are each compressed into a 1”x1.5” Zoom square

- And more (add your own here)

It’s anything but equitable. So, while we eagerly await technology that aligns with our senses in a less awkward (and more humanized) way, there are steps we can take to adapt physical spaces.

At ThinkLab, we have long been fascinated with researching coworking spaces, because they take something that is normally free (workspace from your employer) and monetize it, creating workplace “consumers” that pay for the features that best suit them. Interestingly, while many think of coworking as made up of open plans, much of the data we have reviewed over the past decade suggests that some of the first spaces to sell out, or sell at the highest rates, are private offices. Some have recently suggested the idea of flipping how we use open and enclosed spaces: Meetings could be held in open spaces, using flexible space separators, attention to acoustics, and analog tools like whiteboards, while individual work would happen more in enclosed pods or enclaves.

We’ll be exploring this topic further on Clubhouse on May 20, 2022 in our club Design + Data w/ThinkLab, and we invite you to join us and join the conversation.

We’ll be exploring this topic further on Clubhouse on May 20, 2022 in our club Design + Data w/ThinkLab, and we invite you to join us and join the conversation.

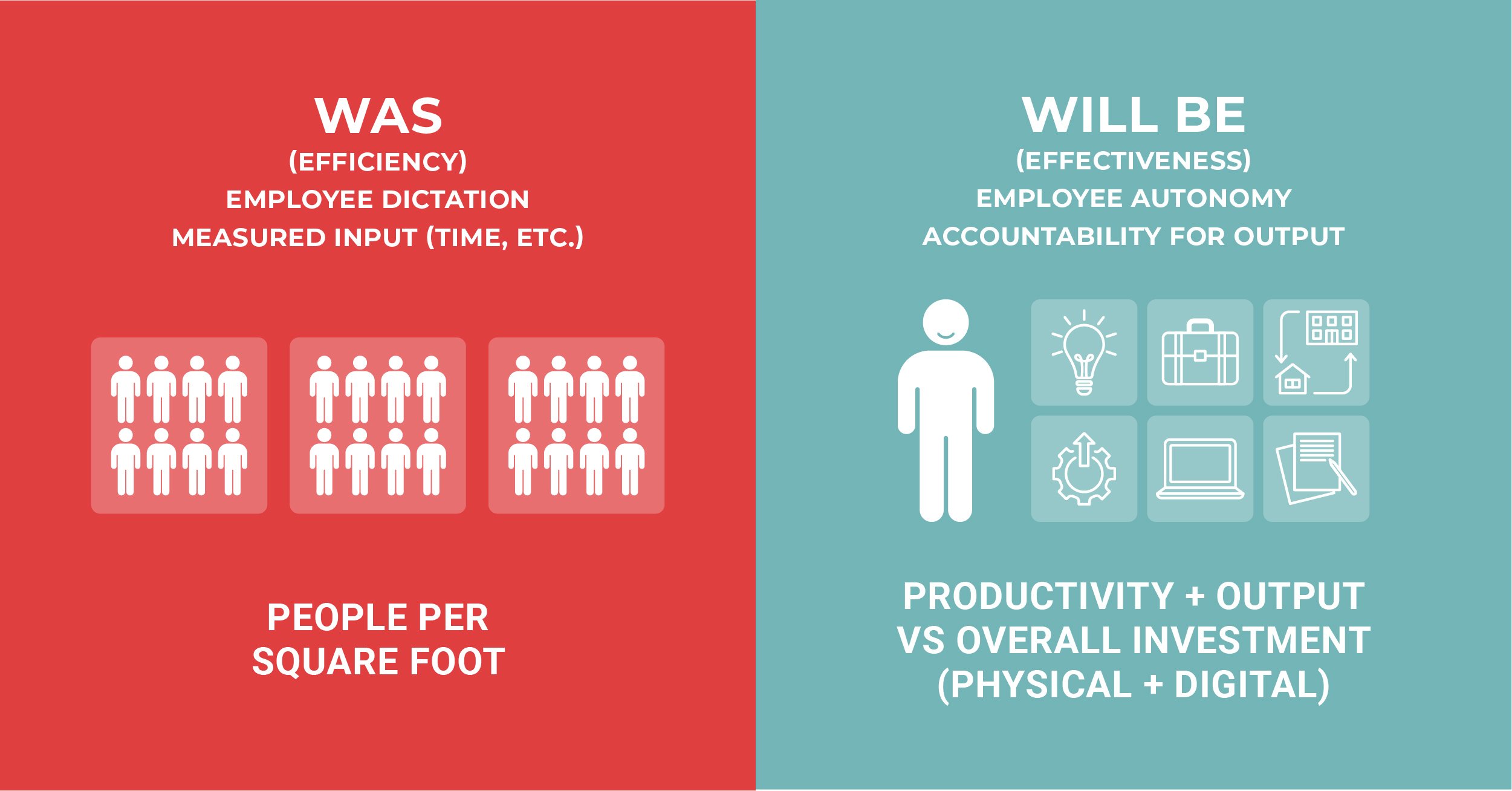

Evolving “measures of success” to focus on effectiveness over efficiency.

Perhaps our long-standing focus on efficiency measures have been driving the wrong decisions. “An underlying thread is that we have neglected people,” says Lister. You can see it “when you walk into a space and everyone is wearing headphones, because they can’t hear themselves think, when people’s most common complaints are [about] noise, temperature, and coffee. We need to meet those most basic needs of people for them to perform at their best,” says Lister.

It’s true that “people per square foot” is easy to measure and makes sense in spreadsheets, but if we consider humans as our most valuable assets, and their productivity as the most valuable output, those types of measures may not be the most conducive to promoting well-being.

Folger notes, “For 100 years, we have been measuring in $/sq. ft. and people/sq. ft. We need a new way to measure our space. There has been an intimacy to work in the last couple years; we have discovered a lot about how we perform best. The science of how we work best should be completely recognized in the new work model.” According to Folger, this leads to “a huge boost in performance, feeling engaged, feeling happy. The bonus is huge if we just pay attention to it.”

Lister agrees: “We have known since the ’50s that people want autonomy, flexibility, and purpose. Somehow, we have to infuse the physical and virtual space with purpose. Why are we here? What is the culture? Why would I want to go to the office? What’s in it for me? That’s what space needs to answer.”

Lister suggests that a workspace must be a draw, attracting workers like flies to honey, rather than a requirement. This will be no easy task, because as we know, hybrid is the hardest. Now is the time to do the work: to explore how we can help our employees work when, where, and how they work best and making sure the employer gets what they need from their employees. Those who figure this out will create internal cultures that win the war on talent.

Folger adds, “I think this new model and the opportunities in front of us can produce two things that were historically not able to be combined: higher performance and higher happiness. To have choice and voice to work in the way we can best, we have to do that.”

Design physical space to be flexible in an era of disruptions.

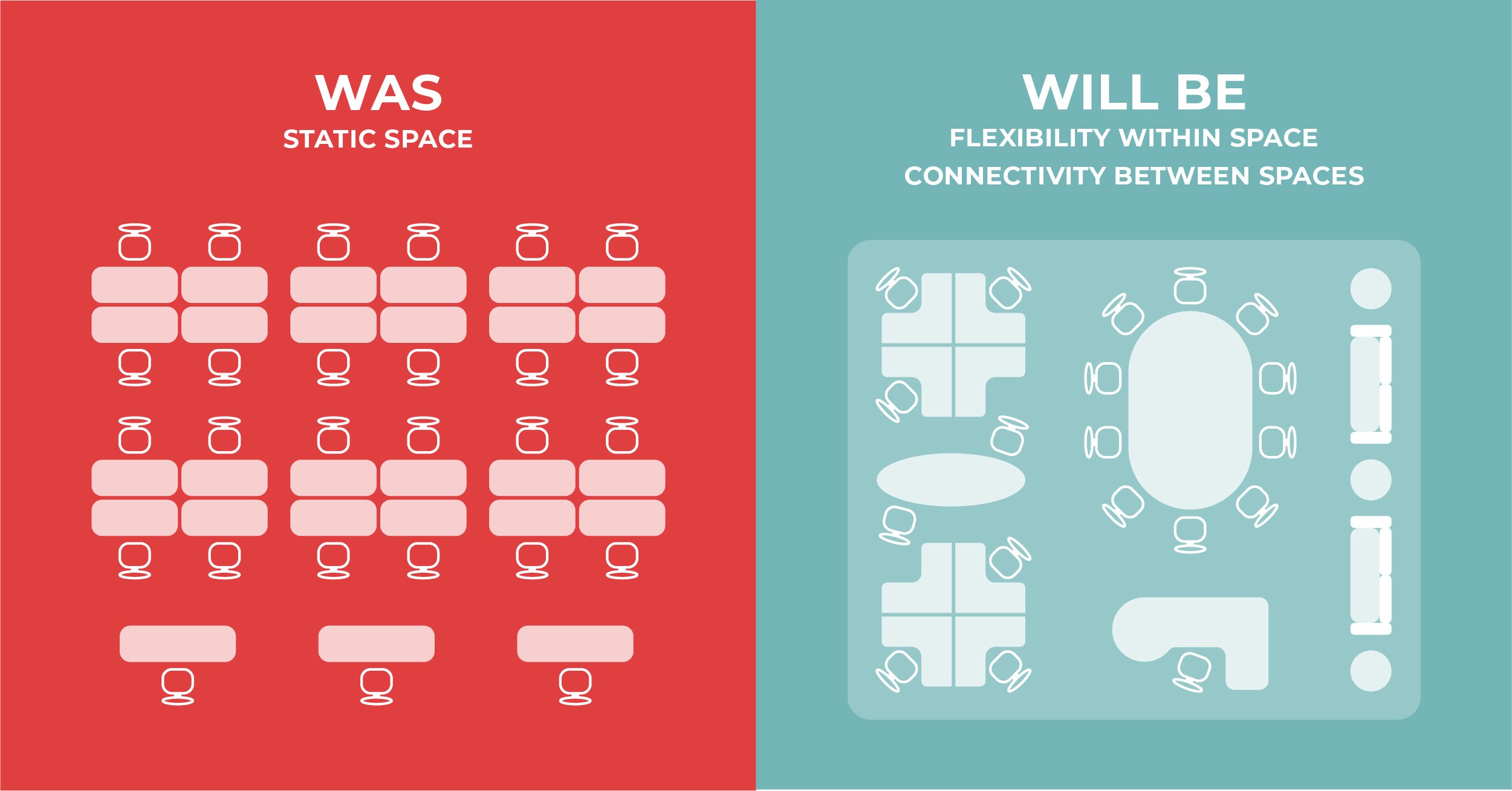

If recent history has taught us one thing, it’s that flexibility is key. And with so many historically decade-long leases and static spaces, there is a great opportunity to explore how flexible spaces can support human needs in an era of ongoing disruptions. This may be as simple as creating multipurpose spaces that can double as a lunchroom, yoga space, and event space by using movable furniture. But it goes beyond thinking of each individual space in isolation. As the rise in coworking and shared tenant amenities shows, sometimes flexibility is not developed within one space, but within the connectivity of many spaces at convenient proximity.

Folger and his team at A+I have spent years exploring public space and the links between spaces. He shares, “When we approach a tenant space, we always approach it for more than beauty, but for business outcomes as well. We [have] brought the same awareness and the same level of strategy and solving for what the community wants to public spaces. The blind spot we are uncovering is that, especially in mixed use, the expertise by space is siloed, but there is no one who is master-planning the experience through all of those connected pieces.” He suggests that figuring out this connectivity and flexibility not only within individual spaces but also those that connect them will be crucial.

Folger closes us with this thought,

“There are some companies who are seeing [recent disruptions] as an opportunity to gain a massive competitive advantage over their competition. We see companies that are doing a lot of talking — talking about prototyping, making bets on the workplace. People are realizing that we can’t bring people back to the old model, and we need to align our physical space with how we want to see the world. And those who are embracing that thinking are raising the bar across the corporate globe.”

Amanda Schneider is President of ThinkLab, the research division of SANDOW Design Group. At ThinkLab, we combine SANDOW Media’s incredible reach to the architecture and design community through brands like Interior Design Media, Metropolis, Luxe, and Material Bank with proven market research techniques to uncover relevant trends and opportunities for the design industry. Join in to explore what’s next at thinklab.design/join-in.